How “CBAM” affect global trading

The European Union’s implementation of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to reduce the risk of carbon leakage as it strengthens its Emission Trading System is likely to push consumer prices higher and affect metal trade flows. It will also force producers globally to accelerate efforts to cut their carbon footprint. By confirming that a […]

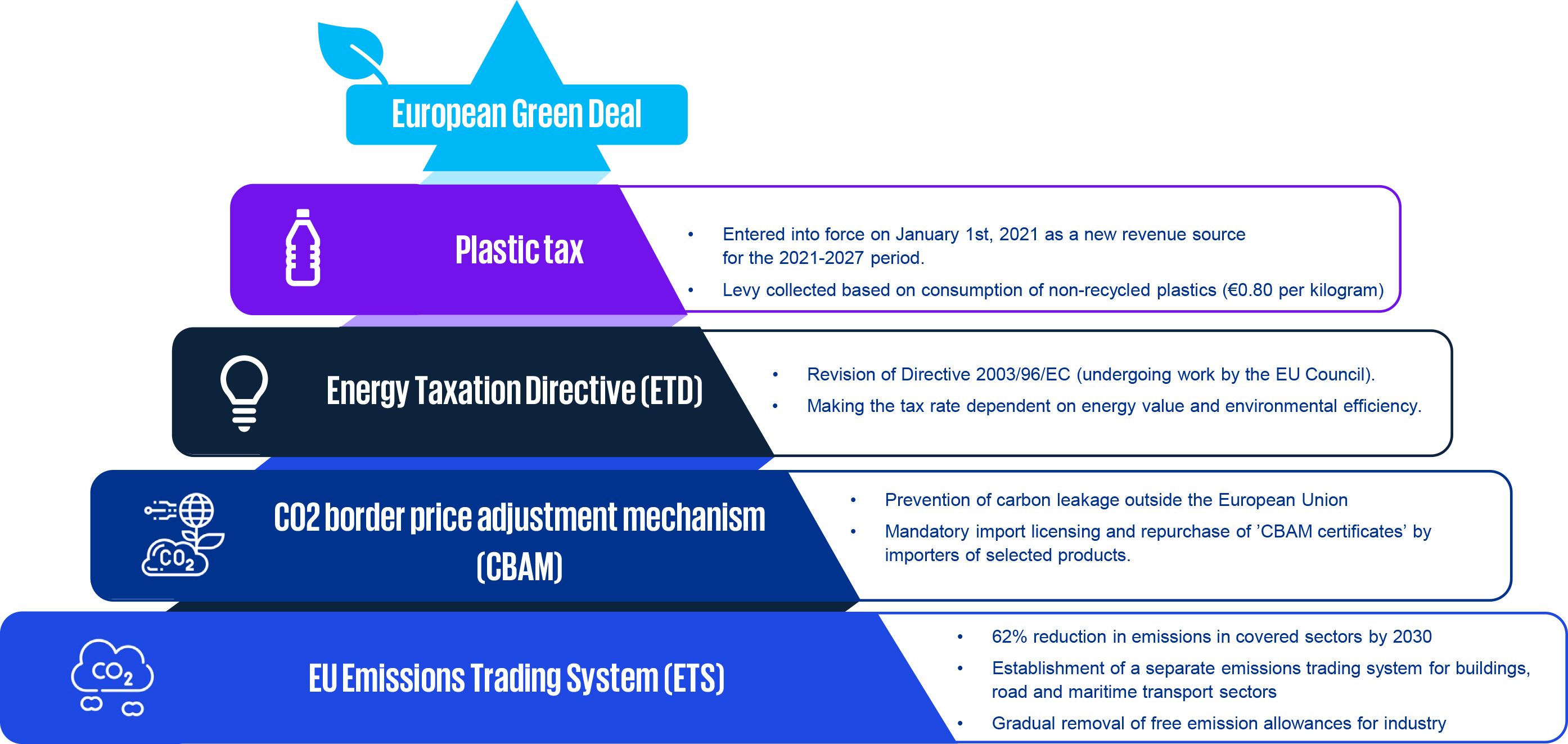

The European Union’s implementation of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to reduce the risk of carbon leakage as it strengthens its Emission Trading System is likely to push consumer prices higher and affect metal trade flows. It will also force producers globally to accelerate efforts to cut their carbon footprint. By confirming that a price has been paid for the embedded carbon emissions generated in the production of certain goods imported into the EU, the CBAM will ensure the carbon price of imports is equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production, and that the EU’s climate objectives are not undermined. The CBAM is designed to be compatible with WTO rules. CBAM will apply in its definitive regime from 2026, while the current transitional phase lasts between 2023 and 2026. This gradual introduction of the CBAM is aligned with the phase-out of the allocation of free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to support the decarbonization of the EU industry. The EU’s introduction of the world’s first Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – will have profound consequences for world trade. By pricing the carbon embedded in imports of certain goods at the same price as domestic emissions, the bloc hopes to incentivize the decarbonization of global supply chains while also protecting its local producers from being undercut. Carbon-intensive sectors such as steel, aluminum, and fertilizers will be first hit by the levy, with other industries and products set to follow later in the decade. Although it is first and foremost a climate-related measure, CBAM will be administered at the border by importers and customs authorities, just like a traditional tariff.

Those impacted can be broadly broken down into non-EU producers, EU end-users, and overseas governments. Each will be faced with a set of compliance and strategic issues to consider as CBAM starts to take effect from October 2023. In many situations, non-EU manufacturers will have to deal with concepts related to carbon price and emissions calculation for the first time. They must ascertain which of the impacted products they ship to the EU in the near future and calculate the embedded carbon emissions of each using the methodology approved by the European Commission. To guarantee that their goods continue to transit through EU borders without a hitch, this information will subsequently need to be forwarded to their importers. Non-EU producers must decide whether and how to decarbonize their own products and processes in order to remain competitive in the EU market once these compliance duties have been fulfilled in the medium term. EU end-users are the people who buy CBAM products, which are frequently essential components used in a variety of industries, including packaging, agriculture, and the automotive and construction sectors. If importers pass on CBAM costs to these end users, the cost of their carbon-intensive imports will increase in comparison to EU or low-carbon alternatives. This will be especially true after 2030 when producers in the EU will have lost about half of the free ETS credits they currently receive. In order to properly handle the implications, end users will need to reevaluate their procurement strategy and give carbon footprint and pricing equal weight. Governments will also have to think about how it would affect their export plans and economies, in addition to businesses. Countries will have to consider their own “carbon competitiveness” as a result of CBAM, or whether their exports’ high carbon intensity puts them in danger of being excluded from global value chains. Based on preliminary evaluations of the CBAM’s effects, nations like China, South Africa, Brazil, India, and Turkey may have major difficulties because they presently export substantial amounts of goods to the EU, including fertilizers and steel.

Trade patterns will be permanently impacted by the decarbonization of global trade flows. Traditional production characteristics like land, labor, and capital no longer solely determine how competitive the goods produced by exporting nations are. In areas and industries subject to a carbon pricing scheme, the cost of carbon incurred during the manufacture of goods already constitutes a significant cost factor. Producers and exporters in third countries are also affected by these economies due to carbon border adjustment mechanisms like the EU CBAM. Agreements, whether bilateral or international, between nations having CBAMs may contribute to the reduction of these obstacles. Perhaps a new generation of free trade agreements (FTAs) with an emphasis on trading in carbon will build on ideas like climate clubs. States that have comparable domestic carbon regulations (and carbon pricing) may decide to waive their different CBAM regimes for commodities that are exchanged between them (but keep the import tax on third-country goods in place).

This article is a part of the class

“751447 SEM IN CUR ECON PROB”

supervised by

Asst. Prof. Napon Hongsakulvasu

Faculty of Economics,

Chiang Mai University

This article was written by Chuyi Luo 641615501